Celebrating Arabic will likely continue for many centuries to come. Arabic is not under threat as many would like to have us believe. Yes there are cultural invasions, facilitated by different media technologies whether in traditional form such as newspapers, radio and television or the internet, website and social platforms.

This is together with the “pigeonisation” of the language and mixing it with English, popularly known as “Arabizi” but these could be argued as no more than fads to set off the alarm-bells ringing.

In reality, Arabic will continue as a strong force because of the fact that many millions and millions speak it or learn it as a medium of instruction. Around 420 million across the Arab nation speak it on a daily basis and there is the fact there are 1.5 million Muslims around the world as far as Indonesia, China, Pakistan, India, Afghanistan to Turkey, Albania, Bosnia, to Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Tanzania who learn the language because of its religious Islamic association and as important cultural tools.

Arabic has come to be seen as a dynamic language of vitality and expression which it will continue to be prominent among its people, institutions, mosques, religious establishments, in its books, literature, essays, poetry, culture and media.

Despite the power politics that has reduced the Arab world to a sub-sphere of super-power/s and great-power rivalries, lynch-pinned through the oil economies, consumerism, strong purchasing ability and different stages of development, the Arab region remains a towering beacon.

This is due to the strength of its language and seen as much by the United Nations when it recognised Arabic as one of its official languages in 1974, joining the other official languages of Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish. The status of the language was further reinforced when the UN, at the behest of Unesco, made December 18 World Arabic Language Day to be celebrated every year.

This point was emphasised thus. “World Arabic Language Day is an opportunity for us to acknowledge the immense contribution of the Arabic language to universal culture and to renew our commitment to multilingualism.

Linguistic diversity is a key component of cultural diversity. It reflects the wealth of human existence and gives us access to infinite resources so that we may engage in dialogue, learn, develop and live in peace,” stated the Unesco director-general Irina Bokova as the Day was officially designated in 2012.

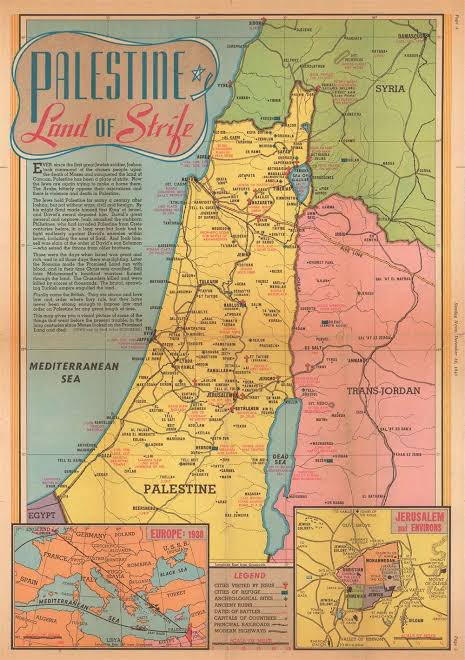

Clearly, the designation didn’t come out of thin air, but reinforced by its centuries-old cultures, development, creations and innovations, going back to the Middle Ages and beyond when Islam was established as a religion and knocked on the doors of Spain and the European continent in the west, to Iran and the modern-day republics of southern Russia to India, outer rims of China and Southeast Asia.

Inherent in this is the cultural historiography that took place within its womb, as emphasised by the contributions and enlightenment of the Islamic religion through the Arabic language and culture. Its manifestations was created by its scholars, coming on the scene in the field of science, medicine, astronomy, literature and philosophy spread out in the different capitals of the Islamic Empire, of Baghdad, Damascus, Egypt, Tunisia, Marakesh and onwards across the Mediterranean to Sicily and Muslim Spain which even today has the remnants of a bygone heritage, architecture and features of an Islamic age.

It was historically argued that Arabs were great translators. They took the Greek works on science and medicine and translated them into Arabic. When the Europeans needed them, and couldn’t find them, they reverted to Arab translations to gain insight.

The great Harvard historian of science George Sarton wrote as much in his Introduction to the “History of Science”. “From the second half of the eight to the end of the 11th century Arabic was the scientific, progressive language of mankind … When the West was sufficiently mature to feel the need of deeper knowledge, it turned its attention, first of all not to the Greek sources but to the Arabic ones.”

These Arabic sources proliferated with increasing numbers and in different fields. Names such as Khaled Ibn Yazid Ibn Muawiyya, Jabir Ibn Hayyan, known in the West as Jabir, became distinguished in chemistry or alchemy as it was known then.

He laid the basis, experimenting in chemical reactions such as crystallisation, calcination, solution and sublimation that are now basic in the study, and were later advanced by scientists in the West who were given the basic tools to advance further.

Jabir also studied metals and described the process of preparation for steel and is credited with discovering red oxide, bichloride of mercury, hydrochloric acid, nitrate acid and many others that began to be used in the West during the Middle Ages. This is also something he documented in his books that were later translated in Spain where a special college was established for translation in Toledo.

Besides that, another Arab scientist came on the scene by the name of Mohammad Ibn Zakariya Al Razi. A didactic philosopher of science, it is said he was learned in every branch of science — not only in chemistry but mathematics, logic, metaphysics and music. But unlike Jabir, he was a man who advanced medical knowledge.

He wrote more than 100 medical books, 33 on natural sciences, 11 on mathematics and 45 books on philosophy, logic and theology. His books and works show his “encyclopedic” capabilities. He came to be an authority in the West.

Next came Abu Ali Al Hussian Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna and nicknamed in Europe as the “Aristotle of the Arabs” because of his wide knowledge in literature and medical, philosophical and scientific works, as well as Islamic law.

He lived between 980-1037, and was sought after by statesmen of the time because he was seen as a well-learned physician with the ability and intuition for advanced medical knowledge. It must be said that as well as Spain, Arab discoveries went through the European continent also via Venice as many European writers testify to that.

What’s also interesting is that English novelists such as William Shakespeare and later modern ones such as Ken Follet acknowledged this in researching his books — and wrote about them in his novels on the Middle Ages, “Pillars of the Earth” and “War without Ends”. The references made here and there gave the reader the impression that the Arab civilisation that then existed was far richer than the one in the West, and despite the slow transport, was reaching distant corners of Europe and England. Such a rich tapestry is only the tip of the iceberg. There were many scholars who have not been mentioned but two will suffice.

The first is Mohammad Ibn Musa Al Khawarazmi, who travelled to India, came back and introduced the Hindu numerals and the concept of zero into the Arab world and popularised it as an easy form of counting and using the decimal system as more practical rather than the awkward and unwieldy Roman system which involved letters and used in Europe at time. By this method mathematics was greatly simplified and became more important to science, architecture, economy, business and general development. This was in 873. At first it is said the West laughed at the 0 but they later saw how valuable it is.

The other is Ibn Al Haytham, who was born in Basra in Iraq at about 945 AD and made major contributions in the physics branch of optics. Later on many learned scholars suggested there were striking parallels between Ibn Al Haytham and the 17th century English Issac Newton who is arguably one of the greatest scientists of all time.

The achievements of Ibn Al Haytham might be more important today than it was then as he talked about important properties such as light rays, the fact that light travels in a straight line and luminous objects that radiate light and light sources.

He developed his theories through what he called scientific method, and become related to the theory of gravity and the theory of relativity. And hence, it is argued Ibn Al Haytham laid the groundwork for the relishing of such ideas not only to be used in the West but for the benefit of mankind.

These scholars and ideas became the basis of world civilizations. The fact that the Arab and Islamic world are much less powerful today than they were doesn’t really say much. This is because today’s technologies made by great powers, whether it’s in the West, Russia, China, Japan must be seen as the sum total of what had gone on hundreds of years ago and which started Arab scientists.

This is an archival piece that was originally written for Gulf News and reprinted on one of the UNESCO websites.