Palestinian Released After 21 Years in Jail

In pictures | In an emotional and long-awaited moment, Hassan Bahar Al-Dam was reunited with his family in Askar refugee camp, Nablus, after spending 21 years in Israeli captivity. His release was part of the prisoner exchange deal secured by the Palestinian resistance.

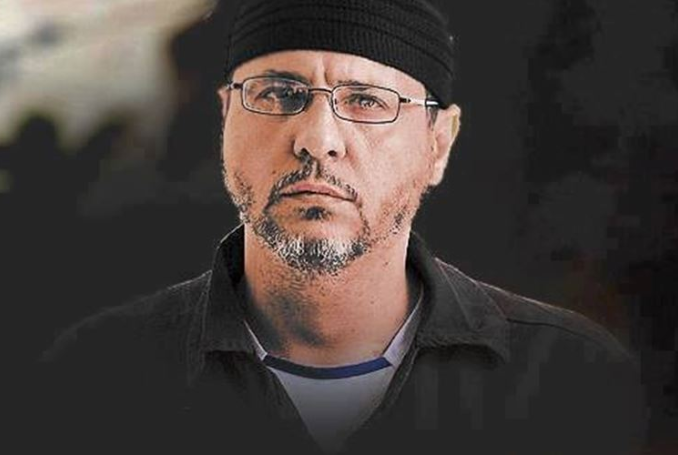

Profile: Meet ‘Prince of Shadows’ Abdullah Barghouti

Nicknamed “the Prince of Shadows” Abdullah Barghouti is the Palestinian political prisoner with the most number of life sentences ever given to a single detainee.

A former leader of the Hamas’ al-Qassam brigade’s armed wing, in the West Bank, he now appears to be on the verge of release in the Hamas-Israel prisoner exchange.

Born in Kuwait in 1972, Abdullah Barghouti grew up outside of occupied Palestine, despite his family having originated from the village of Beit Rima, located near Ramallah. Barghouti attended school, up until high school in Kuwait.

Upon the eruption of the first Intifada in the occupied Palestinian territories, in 1987, Barghouti recounted in his memoir that the uprising had inspired him to seek revenge against the occupiers, especially after Israeli forces murdered one of his cousins and youngest uncle. “Simply put, they threw stones at the Zionist occupation forces that were wreaking havoc, so they were shot and martyred” he stated.

During the first Gulf War (1990-1991), Abdullah Barghouti was reportedly arrested for around a month after being accused of participating in the fight against US forces, later being released after the war. Prior to this, Barghouti had decided to pursue the combat sport of Judo and was trained by a man named Munir Samik who was also Palestinian.

Samik once asked Barghouti: “Aren’t you Palestinian? Don’t you want to liberate your country? If you use it against all those who occupied your homeland, there in Palestine, use what you learned here.” Inspired to make himself physically strong and capable of fighting Israel, he then began training in the use of firearms and explosives in the Kuwaiti desert. During the war, Barghouti’s family was forced to flee to Jordan.

When he traveled to live in Amman, Jordan, he would finish high school there but due to his family being too poor to afford University, so he would borrow money from a relative in order to open up a mechanic shop, continuing to practice Judo as a hobby. However, he wasn’t able to earn enough money to keep his business afloat and pay back his relatives and decided to move abroad in order to pursue higher education instead.

A friend of Barghouti had recommended he apply for a visa program to travel to South Korea, which ended up leading him there in pursuit of an education. When he arrived, he had no money and little but the clothes on his back.

Barghouti walked from the airport to a location that was supposed to help him secure an education; his journey would take three days during which he went without eating. He recalled that he drank water from public parks until reaching the address he had been given, finding out that it was a wood-cutting factory.

So, without any money or prospects, he ended up working at the factory for 45 days without having money to buy food, eating only from what the factory would supply him.

In 1991, after a few months in the wood-cutting factory, he moved to work in a mechanical factory and studied in parallel with his work at an engineering institute, specializing in electromechanics. This was also the time during which he would meet his wife, who was of Korean origin.

However, his passion for seeking the liberation of Palestine through armed struggle would not perish while he lived in South Korea, as he would routinely go deep into the forest and practice making improvised explosive devices and refining his craft. In 1998 he would then return to Amman with his wife, before deciding to divorce her due to his desire to have children.

Around this time he started becoming more religious, moved to Jerusalem and then the West Bank, married a Palestinian wife, and settled down in his family’s village of Beit Rima. He later had two daughters, Safaa and Tala, and a son called Osama.

It just so happened that in 2001, Beit Rima would be the first area in the West Bank that would experience a full-scale military invasion during the Second Intifada. Israeli forces deployed tanks, attack helicopters, and a huge military force to the village.

Abdullah Barghouti joined the Qassam Brigades in 2001, seeking out his cousin Bilal Barghouti in order to share his expertise in bomb-making.

After his cousin, who is currently serving 16 life sentences in Israeli military prison, witnessed how skilled he was at engineering explosives, he told his superiors in the Hamas military wing and Abdullah Barghouti would begin military training in the Nablus area, going on to become a commander of the Qassam Brigades in the West Bank.

This entire time, almost nobody close to him knew of his secret ambition to seek revenge against Israel and his bomb-making skills. He would later go on to participate in the manufacturing of explosives that killed 66 Israelis and injured over 500.

When he was eventually tracked down in 2003 and arrested by the Israeli occupation forces, he was interrogated and tortured for over five months, before being handed 67 life sentences, amounting to 5,200 years in prison. In later interviews recorded with Barghouti from inside an Israeli prison, he would confidently state that one day interviewers would come to meet him while he sits inside a hot tub in Ramallah.

If he is to be released during the upcoming Hamas-Israel prisoner exchange, it is likely that Israel will request his deportation outside of occupied Palestine. It is speculated that Barghouti could be useful to Hamas in developing its influence in the armed struggle inside the West Bank, which is currently dominated by Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) and Fatah-aligned fighters.

(The Palestine Chronicle)

– Robert Inlakesh is a journalist, writer, and documentary filmmaker. He focuses on the Middle East, specializing in Palestine. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.

The Teacher Tests World Audiences to Think Palestine

Oscar-nominated and BAFTA award-winning Palestinian-British filmmaker Farah Nabulsi is calling for global empathy for Palestinians through her debut feature film, The Teacher.

In an interview with Anadolu, Nabulsi said her goal is to challenge audiences to reflect on the hardships Palestinians face under occupation. “I really want people to ask themselves: Is this a reality they would accept for themselves? And if it isn’t, why have Palestinians been expected to?”

Nabulsi shared her experiences filming The Teacher, which premiered at the Toronto Film Festival on Sept. 9, 2023.

“Given the current reality in Palestine, as Israel conducts a genocide in Gaza, I hope this film offers a deeper human context to that reality. The sociopolitical is important but often missing from the discourse.”

Born and raised in the UK, Nabulsi said a visit to Palestine a decade ago profoundly changed her perspective.

“Despite thinking I knew about the injustice and discrimination, witnessing it firsthand—checkpoints, demolished homes, detained children—was shocking,” she recounted.

“This injustice hit me deeply,” she continued, explaining that storytelling became her way to process and respond.

Drawing inspiration from real life

Nabulsi said the script for The Teacher was shaped by her conversations with Palestinians and her observations during her time in Palestine. The film addresses settler violence, home demolitions, and the treatment of children in military courts.

Referring to a 2011 exchange where an Israeli soldier was released by Hamas in return for over 1,000 Palestinian prisoners, Nabulsi highlighted the disparity in the perceived value of human life.

“It’s this idea that Palestinian lives are not valued like Israeli Jewish lives. That imbalance inspired the story,” she said.

“I never could have imagined, though, the exponential magnification of that imbalance, as we now witness hundreds of thousands of Palestinians being killed, maimed, starved, and subjected to malnutrition and disease in Gaza.”

Filming amid real-life injustices

Filming in the occupied West Bank brought emotional and logistical difficulties, Nabulsi said.

“I didn’t realize how emotionally taxing it would be to witness these injustices while shooting scenes replicating them,” she said.

“It’s different from reading about it or watching it on the news. When your cast and crew have lived through these realities, you feel a responsibility to do justice to their experiences. It takes a mental and emotional toll.”

The film was shot near the village of Burin, close to Nablus in the occupied West Bank, where challenges arose during production.

“We heard that illegal Israeli settlers had descended onto the village, torching olive groves—something depicted in the story itself. On another occasion, I encountered a family with six children standing before the rubble of their freshly demolished home, an act mirrored in the film.”

Nabulsi said she hopes her work will inspire audiences to empathize with Palestinians and support their pursuit of freedom.