Mohamed Jabaly, Palestinian filmmaker from Gaza, has lived through extraordinary circumstances. Born during the first intifada and raised during the second, Jabaly’s life has been shaped by the relentless turbulence in his homeland.

Now residing in Tromso, Norway, his journey is a testament to resilience, displacement, and the power of storytelling.

Jabaly’s path to Tromso, however, was not a straightforward one. “Tromso and Gaza, in the first place, are twin cities,” he tells Anadolu, referring to the long-standing relationship between the two. In 2013, a Norwegian delegation screened one of his short films in Gaza, marking the beginning of a meaningful connection. “They invited me in 2014 to visit Tromso and be a part of the film festival there.”

However, life in Gaza rarely follows a predictable script. The summer of 2014 brought a 51-day assault on the blockaded enclave, delaying Jabaly’s departure. Amid the chaos, he joined an ambulance unit, capturing the harrowing reality of frontline responders. This footage became his first feature documentary, Ambulance.

“Shortly after the attacks, I traveled to Tromso,” he recalls. “What was supposed to be a one-month visit turned into seven years.”

Two weeks after his arrival, the Rafah border closed, trapping him in Norway. “I decided not to seek asylum. Instead, I applied for an artist visa, and that’s when this whole journey began.”

Starting from below zero

Life in Tromso was a stark contrast to Gaza. Jabaly describes his first winter in Norway with characteristic candor. “It was dark, below zero, and everything was new. I had never touched snow in my life,” he says. Adapting to this unfamiliar environment was not just a physical challenge but an emotional one as well.

“Being far from my family, my friends, my city … that was the biggest challenge,” he says. With limited resources, he relied on the generosity of friends who hosted him. Volunteering at film and music festivals allowed him to contribute to his new community while earning small amounts to survive. “Norway is an expensive country, but I managed to stand on my feet. I started from below zero, not just with the temperature but in life.”

Capturing the human impact of displacement

Jabaly’s second feature documentary, Life is Beautiful, chronicles his experience of being caught between two worlds: the homeland he could not return to and the foreign land he had to call home. “It puts new names and faces into the struggle of displacement and statelessness,” he says. The film not only highlights the challenges of being a Palestinian in exile but also raises awareness about the broader human struggle of stateless individuals worldwide.

“In Palestine, I was always Palestinian. In Gaza, I was always Gazan. Suddenly, I’m considered stateless,” he explains, touching on the complex legal and emotional terrain of his identity. “I didn’t make the film just to make a film. I wanted to shed light on our human struggle and fight the term ‘statelessness.'”

The indelible mark of Gaza

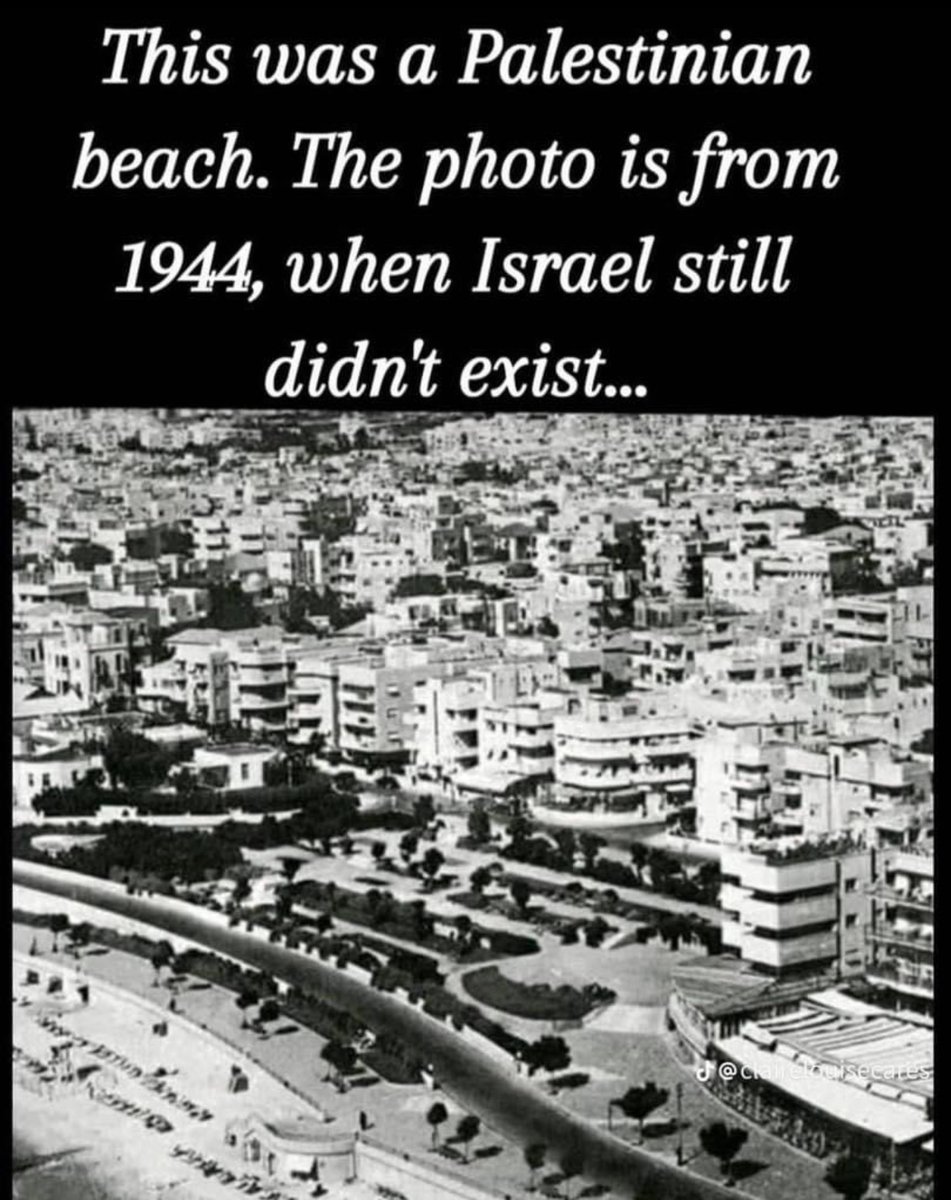

For Jabaly, Gaza is not just a place; it is an integral part of his identity. “You cannot escape from your identity,” he asserts. “Being from Gaza became even more special today with what’s happening. But all Palestinians share the same struggle. We try to raise awareness and insist on our freedom.”

This deep connection fuels his work. “If life had been normal, I wouldn’t need to make films about freedom. But I was born into a struggle, and that’s what drives me to tell our stories.”

Looking ahead

Despite the heavy burden of his past and the ongoing challenges facing Gaza, Jabaly remains hopeful. “I imagine having a film school in Gaza in five years,” he shares. “If life gave me normalcy, I would build things. But for now, I feel compelled to make films about war and our human struggle.”

As for his immediate plans, Jabaly’s work continues to be shaped by the present-day realities of Gaza, where Israel has killed more than 45,000 people since Oct. 7, 2023. “It’s difficult to be creative when your mind is occupied with worry. But we have to insist on our narrative and raise awareness for future generations.”

‘Life is beautiful’

Jabaly’s unwavering optimism shines through, even in the face of despair. “I named my film Life is Beautiful because I hope one day life will be beautiful. If not today, maybe tomorrow, or next year.” It is a sentiment that encapsulates his journey and his vision — a reminder that even amidst the darkest times, hope persists for a new dawn.

(@ihcentoo)

(@ihcentoo)